Hints to the Stormy Past

Record of the Month!

April is a busy month, with well over fifty nationally

recognized movements, industries, heritages, and histories observed on a daily

and weekly basis, as well as all month long. Additionally, April is filled with

the anniversaries of several positive and negative historical events, including

the first presidential assassination in American history, as well as the

beginning and end of the American Civil War. While little mention of these

events is made in the Commissioners’ Journals, there are a couple of entries

that allude to the fiery trial facing the United States at the time.

The American Civil War started in the early hours of April

12, 1861 when traitors attacked Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South

Carolina. The Fort’s commander, Union Major Robert Anderson agreed to surrender

on April 13, 1861 and evacuated the following day. Despite the nearly 34 hour

bombardment, no casualties are recorded for either side. Fort Sumter is often

noted by historians as being a “bloodless opening” to the bloodiest war fought

on American soil.

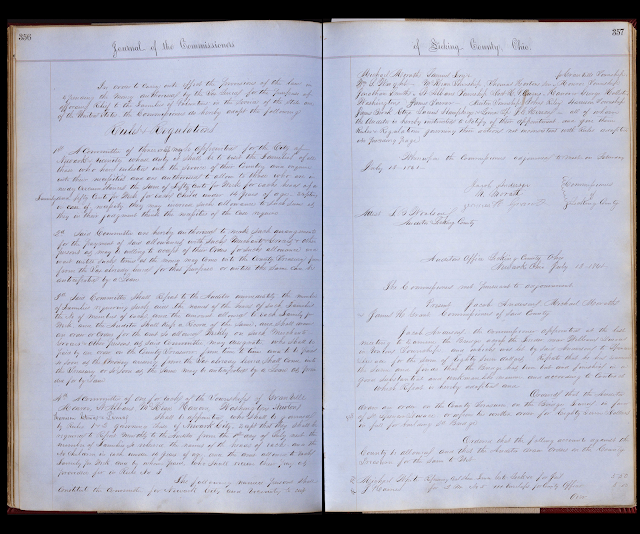

On April 15, 1861, President Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to serve for three months to put down the traitors opposing and obstructing the laws of the United States. Congress was out of session at the time, so Lincoln further requested that Congress hold a special session on July 4, 1861. In a message to Congress, Lincoln defended his original call for volunteers and requested additional troops and funds to ensure the preservation of the Union. In Licking County, the Commissioners passed a resolution to distribute relief funds to the families of those volunteering to serve their country (Commissioners’ Journal Vol. 1 pg. 356-357).

The war would last four years and cost the lives of over 620,000 Americans, while freeing 3.9 million African-Americans from the heinous crime of slavery. Fighting in the east would end on April 9, 1865, with Lee’s surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia, which made the largest part of the fragmented traitorous forces. Although, many historians consider Lee’s surrender as the end of the war, the fighting would not cease until May 13, 1865, with the final battle of Palmito Ranch, Texas.

President Lincoln suffered a great deal during his terms in

office, both under the enormous strains of the presidency and war raging across

the country, as well as trying to hold his family together as it grieved the

unexpected loss of William (Willie) Lincoln, age 11. Upon hearing of Lee’s

surrender, Lincoln became infectiously cheerful and hopeful for the future,

according to recollections from Mary Todd Lincoln, Elizabeth Keckley, and

others from Lincoln’s inner circle.

On Friday, April 14, 1865, the President and First Lady

planned to attend a production of Our

American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre with Clara Harris (the daughter of a

friend of the First Lady) and her fiancé Major Rathbone. General Grant and his

wife Julia were also supposed to attend the production, but ended up backing

out at the last minute so they could visit their children. Around 8:30 p.m.

shortly after the play had started, President Lincoln and the First Lady

entered the presidential box. Upon their arrival the other theatre goers and

actors rose applauding and shouting with delight. James Suydam Knox was in the

audience and remembered the “deafening cheers” and that “everything was

cheerful, and never was our magistrate [Lincoln] more enthusiastically

welcomed, or more happy.” The President laughed heartily and made a bow to the

people before settling himself in his rocking chair.

Just after the third act had started, a muffled pistol shot and

yelp was heard, and a man leaped from the presidential box, partially ripping

the flags draped across its front. The man landed awkwardly on stage; facing

the audience, he brandished a dagger and shouted “Sic semper tyrannis, the

south is avenged!” He turned and disappeared through one of the theatre’s back

exits. Knox remembered that “the whole theatre was paralyzed.” Screams from the

First Lady roused the shocked theatre into frenzied action.

The bullet had entered Lincoln’s head around the left side of

the base of his skull near his ear and lodged behind his right eye; he was

losing blood and barely breathing. Lincoln was carried across the street to a

boarding-house opposite the theatre where he was joined by cabinet members,

staff, family and friends; he was unconscious. Despite the doctors’ best

efforts, President Abraham Lincoln died nine hours later at 7:22 a.m. on

Saturday, April 15, 1865.

While this horrific scene was playing out at Ford’s Theatre,

across Washington D.C. Secretary of State William H. Seward and his household

were brutally attacked by another assassin wielding a knife. Seward had been

bedridden for several days recovering from a near fatal carriage accident. Despite

being stabbed several times, Seward was ultimately saved from death by the

metal collar that had been placed around his throat as a result of the accident.

With Lincoln gone, Vice President Andrew Johnson was sworn in

as the new President. Lincoln’s Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, took charge of

maintaining order in the ensuing chaos. In days following these events, an

intense investigation and manhunt for the conspirators was launched, and

arrangements for Lincoln’s funeral were made. Before the end of April, all the

conspirators were either rounded up awaiting a military tribunal, or dead. It

was decided that Lincoln should be laid to rest in his home of Springfield,

Illinois. The train that would take his body and the body of his son Willie to

Springfield would retrace the route he had taken as President-elect in 1861.

The train passed through Ohio, stopping in Cleveland and Columbus, where Lincoln

was laid in state in the rotunda of the Statehouse on April 29, 1865. While

Lincoln’s train did not pass through Licking County on its journey west, the

Licking County Commissioners had the Courthouse decorated with black cloth as a

sign of respect (Commissioners’ Journal Vol. 1 pg. 544-545).

To see all of the sources used to write this article, please check out the Bibliography Page. If this information interests you, please feel free to contact us by phone at 740-670-5121 or email archives@lcounty.com.

.jpg)