Student Resources

Record

of the Month!

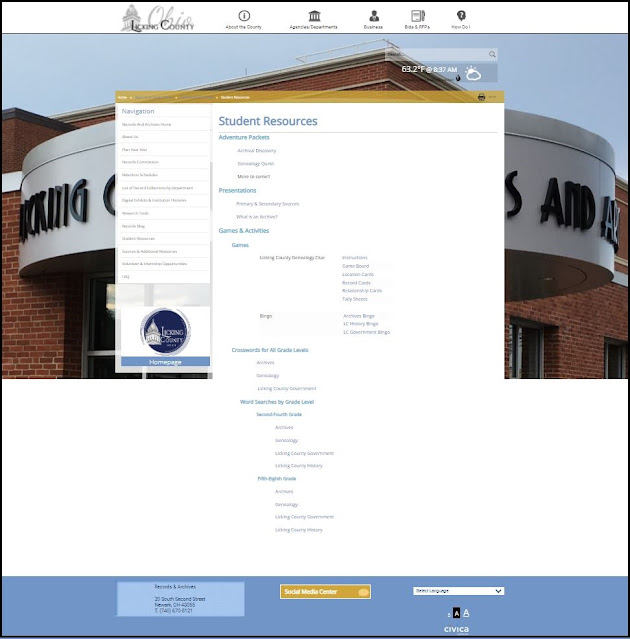

For the month of August, as students reluctantly begin preparations for the upcoming school year, we have decided to feature the Student Resources

page of the Licking County Records & Archives website. Also included with

this post is a short research/writing guide for older students.

The Student Resources page has activity packets, puzzles, and more that focus on archives, genealogy, government, and history. While some of the resources being offered on the Student Resources page are geared towards grade school students, other things such as the Primary & Secondary Sources presentation and Bingo cards are meant for all to enjoy!

In honor of the research papers that will soon be written, we

here at the Licking County Records & Archives Center offer this short

research/writing guide. While this guide is geared towards older junior high

and high school students, we hope it will be helpful to anyone who reads it.

The very first thing that you should do is to ask yourself what do I want to research? In school

there are times when this question will be answered for you, though whenever

you have the choice you want to pick something that holds your interest (if you

don’t find it interesting, how will anyone else?). If you do get stuck with a

less than thrilling topic, then you should see if you can find ways to connect

it to something that interests you more (pro-tip: arguing the connection

between two topics can make for an impressive paper if you can demonstrate the

connection with various sources).

Now this is the point where your teacher will start pushing you

to establish a thesis statement based off the topic in order to guide your

research process. For those of you who may just be getting into essay and paper

writing, a thesis statement is the basic premise for your argument: your

conclusions summarized and boiled down into a sentence or two. However,

developing a thesis statement prior to conducting any research is immensely difficult

and results in one sided research—how can you draw conclusions and summarize the

facts before you have any facts to work with?

Instead we recommend developing a number of research questions

to guide your quest. Below are some recommendation for research questions, as

well as some advice on developing more questions.

· What makes it interesting to you? Figuring out why something catches your interest can help you focus your research. Additionally, answering the question can make you aware of any subconscious biases that you may have that could impact your research. When conducting research you want to make sure you look at opposing perspectives/arguments (pro-tip: an opposing perspective is someone who opposes your conclusions and/or interpretations. For example, including information about people who opposed the Civil Rights Movement when writing about the impact of various civil rights leaders does not count as including an opposing perspective. An opposing perspective would be that the civil rights leader you are writing about was more or less significant than you are claiming.) The best arguments provide full support for their premises and conclusions, while also fully and truly addressing opposing perspectives.

· How did you first learn about the topic? Where did that information come from? First impressions are not always correct and misinformation is easily spread when scholars and writers do not fully fact-check their sources. Despite the more recent awareness of the need to fact check, problems with misinformation have actually been plaguing humanity for thousands of years. Fully understanding the difference between and the value of primary and secondary sources takes center stage when we critically evaluate the sources we use to build our arguments-see the presentation slides available on the Student Resource page for more information on primary and secondary sources.

· Where are there gaps? Think about what you “know” about the topic and consider what else you would like to or need to know about it. Ask yourself both general and specific questions about the topic to get a sense of what information to look for (pro-tip: how and why questions are especially helpful in exposing the gaps in our knowledge/understanding of a topic). Your questions may only seem to lead to more questions and that’s okay, because these are your foundations. Answering these questions will direct your research and help you build your thesis statement.

· Where could you learn more about it? One of the most valuable skills to develop is figuring out how to find information. While doing basic web searches can be helpful, being able to deduce where quality information can be found is important to building a strong argument and conclusion. A great place to start gathering sources is the reference or bibliography section of a given source—not only will this help you evaluate that source, it can point you in the direction of other helpful sources. Even Wikipedia reference sections can yield helpful sources, though Wikipedia itself is not a scholarly source and should never be used as a scholarly source. While digital resources are extremely valuable, it is also strongly recommended to visit or reach out to libraries, archives, museum, universities, etc. These institutions have experts and individuals whose sole purpose is to help connect people, such as yourself, to information—and being able to directly ask questions of another person can improve your understanding of the topic.

Now that you know how get started, it’s time to get started. Conducting research can

make you feel like a detective looking for clues (pro-tip: using index cards to keep track

of the information you find can help you stay organized). After you have collected

and read all you can, take a moment to consider the big picture (i.e. what does

it all mean). Think about how all of the pieces fit together, how they impact

each other, and see if you can identify any patterns in the information you

have. Next, try to write out a sentence or two in broad terms as to what you

think and why—this is your thesis statement (ta-da). Your thesis statement will

likely need to be condensed/polished a little so that it fits into a single

statement.

The next step is to organize all of the information you have

and write out in greater detail how it supports your thesis. You also want to

weave in opposing perspectives and explain why, using the facts you have, your

interpretation is stronger than theirs (pro-tip: avoid making the

opposing perspectives appear weaker than they really are when you explain them

and why they are wrong. Making an opposing argument seem weaker than it is, is

called a strawman fallacy. Fallacies are mistakes/flaws in logic, and tend to

appear when there are gaps in the supports to our arguments. The more fallacies

you have, the weaker your argument is and the easier it will be for someone to

present counter arguments against you.)

Now it’s time for your conclusion: Write a short summary of

your main points and why they support your thesis and you are mostly done! The

next step is proofreading and editing, which I recommend doing after taking a

break from researching and writing. Reading with “fresh eyes” will help you

catch a lot of mistakes/typos (pro-tip: start proofreading from the last

paragraph and work your way back to the beginning. Doing this makes it harder

to “get lost” in the flow of the paper on your first read through). Next you

should see if you can find someone you trust to proofread it; peer editing is

not always the most helpful form of editing, so you want to make sure you have

a backup editor. Once you have made any necessary edits and are generally

comfortable with your paper, make sure all the formatting (MLA, APA, Chicago,

etc.) is good and that you included everything in your bibliography, then you

are good to turn it in (hurray)!

If this information interests you, please feel free to

contact us by phone at 740-670-5121 or email archives@lcounty.com.

.jpg)